The Coming of Kull the Atlantean

and the Phantom Empire

By Gilbert Colon

The following is the second in a series of dissection and discussion of select Marvel adaptations of stories first appearing in the pulps. These essays will appear on an irregular basis but we'll make sure to give you a heads up beforehand! We're extremely happy to welcome aboard Professor Gilbert Colon.

Professor, the dais is yours...

Professor, the dais is yours...

“Ho! Awake, Valusia!...Valusia – land of dreams and nightmares – a kingdom of the shadows, ruled by phantoms who glided back and forth behind the painted curtains, mocking the futile king who sat upon the throne – himself a shadow.”

I

A KING COMES

Marvel’s “A Kingdom of Shadows” (Kull the Conqueror #2, September 1971) begins with the story’s second part, “Thus Spake the Silent Halls of Valusia,” the first, “A King Comes Riding,” having received coverage in issue #1 (from which it takes its title “A King Comes Riding!”). This first issue begins with an epic military procession, demonstrating the might of the Valusian kingdom, that would leave Leni Riefenstahl quivering with titillation.

From there it weaves together “By This Axe I Rule!” and “Exile of Atlantis” to tell the origin of Kull and his ascendancy to the Topaz Throne. If some of it feels familiar to moviegoers, it is because the Atlantean’s back story (and nemesis Thulsa Doom, for that matter) were plundered from various Kull tales for the 1982 film Conan the Barbarian (slave, gladiator, wandering adventurer, soldier of fortune, king). Considering the fact that Howard, hereafter REH, plundered himself by rewriting his rejected Kull story, “By This Axe I Rule!,” into the Conan yarn “The Phoenix on the Sword,” this seems perfectly within the bounds of acceptability. The first issue ends with the sentence from “Shadow” that serves as a cliffhanger to lead into issue #2: “And, in a dim nook of the Great Hall, a tapestry moves---slightly--! Next: A Kingdom of Shadows!”

II

THE ART

Marie and John Severin drew Kull a little too similarly to how Barry Windsor-Smith and Sal and John Buscema drew Conan, and beyond both being big brawny barbarians, Kull and Conan should not be interchangeable. Past book covers from Lancer and Bantam have been guilty of the same, and REH bears some responsibility for this – compare his descriptions:

Marie and John Severin drew Kull a little too similarly to how Barry Windsor-Smith and Sal and John Buscema drew Conan, and beyond both being big brawny barbarians, Kull and Conan should not be interchangeable. Past book covers from Lancer and Bantam have been guilty of the same, and REH bears some responsibility for this – compare his descriptions:“Hither came Conan, the Cimmerian, black-haired, sullen-eyed, sword in hand... – The Nemedian Chronicles.” – “The Phoenix on the Sword”

“...the crown of Aquilonia shone on [Conan’s] square-cut black mane; but the great sword at his side seemed more natural to him than the regal accouterments. His brow was low and broad, his eyes a volcanic blue that smoldered as if with some inner fire. His dark, scarred, almost sinister face was that of a fighting-man.” – "The Hour of the Dragon"

“Under heavy black brows [Kull’s] cold grey eyes brooded. His features betrayed his birth for Kull the usurper was an Atlantean.” – “Swords of the Purple Kingdom”

“Kull was tall, broad shouldered and deep chested – massive yet lithe. His face was brown from sun and wind, his square cut black hair like a lion’s mane, his grey eyes cold as a sword gleaming through fathoms of ice.” – “The Black City”

Yet some differentiation still is in order, particularly considering that many issues of Kull and Conan ran concurrently. The obvious challenge for the Severins is to differentiate Kull visually from Windsor-Smith and the Buscemas' Conan, but in the end the sibling team interprets Kull with familiar fantasy barbarian imagery.

Looking back, Weird Tales artist Hugh Rankin’s Kull – a sword-wielding, loin-clothed, broad- and bare-chested barbarian, heavily browed with wild wooly hair and beard – resembles more the Middle Eastern potentates such as Ashurbanipal, Sennacherib, or Darius (see above). In a letter to friend R. H. Barlow (June 1, 1934), REH ranked Rankin a personal favorite of all the artists that illustrated his work in Weird Tales, so it might have been wise to take a cue from the original pulp art.

However the letter column of Kull the Conqueror, the Thurian Chronicles, documents the popularity of the art amongst readers. In Kull the Conqueror #5, one reader, commenting about “the Severin Clan,” identifies “Marie...with the best of the typically Marvel-style art. That is to say, the Romita-Kirby-inspired Buscema style” and attributing to her brother “that Victorian look [that] is essential [for Conan, and especially Kull].”

One enthusiastic letter-writer, in Kull the Conqueror #4, notes that “The Serpent Temples and Serpent Men the Severins drew for this issue looked a lot like Marie’s interpretation of the Serpents in Sub-Mariner #9. Perhaps the Serpent Crown of Naga, or Lemuria itself, could be tied in with Kull’s Serpent Men.”

The Severins take some artistic license at the story’s end by literally visualizing what is absent in REH’s prose, the tiger nature of Kull clashing with serpent imagery on page 18. “Shadow” does call Kull “this tigerish barbarian” and speaks of “the blinding, tigerish speed of [Kull’s] attack...,” and in “By This Axe I Rule!” a character says to him, “I – thought you were a human tiger.” It is a forgivable flourish that provides a panel of primitive totemic power – tiger versus snake, man’s symbolic ancient enemy. (This visual appears several times in issue #1.)

While we will never know REH’s opinion of Marvel’s visual interpretations, REH friend and correspondent Harold Preece, in The Thurian Chronicles, gives his blessing to Marvel’s enterprise: “I used to try picturing in my mind what Kull and Conan and the rest of his colorful swashbucklers would have looked like in real life...Now, thanks to Marvel Comics, another Howard epoch begins – a visual epoch.”

REH’s Weird Tales favorite fictioneer E. Hoffman Price extends his pulp imprimatur with a letter in which, calling Marvel’s adaptations “pure-strain Howard,” he overcomes his initial doubts: “I don’t even have to look at the pictures, though finally I do...I had been thinking, ‘These well-meaning folks will fall on their faces...’ But – the first sheet did it!...this novel experiment is fun, gentlemen...I didn’t expect anywhere near as much as I got. Fact is, I was a bit skeptical...This really has been interesting, and I do not think you could have done the job any better.”

Short of a voice from the great beyond, these pair of quotes are likely as close as we will get to an official endorsement from ages (pages?) past.

III

THE CHARACTER OF KULL VERSUS CONAN

While Wright and readers may have preferred “the more carefree and decisive Conan,” there is evidence that others in REH’s circle leaned towards Kull. REH scholar Glenn Lord contributes an article to Savage Sword of Conan #1, opening his essay “An Atlantean in Aquilonia” with H.P. Lovecraft naming “the King Kull series...a weird peak” and mentioning the affection of Robert Bloch, no friend of the Conan yarns. (At the time of REH’s death, Bloch wrote into Weird Tales these words: “Despite my standing opinion on Conan, the fact always remains that Howard was one of WT’s finest contributors, and his King Kull series were among the most outstanding works you ever printed.”) Lord also points out that Arkham House publisher August Derleth included all the Kull stories extant at the time, but only a fraction of the Conan ones.

Where Conan does gain in wisdom over the course of his adventures, Kull possesses a questing spirit which qualifies him as almost a philosopher-king. A good exercise would be to read the rejected Kull tale “By This Axe I Rule!” alongside the Conan story REH rewrote it as, “The Phoenix on the Sword,” for points of comparison and contrast.

IV

LURKERS ON THE THRESHOLD

“Always he had seen their faces as masks, but before he had looked on them with contemptuous tolerance, thinking to see beneath the masks shallow, puny souls, avaricious, lustful, deceitful; now there was a grim undertone, a sinister meaning, a vague horror that lurked beneath the smooth masks. While he exchanged courtesies with some nobleman or councilor he seemed to see the smiling face fade like smoke and the frightful jaws of a serpent gaping there. How many of those he looked upon were horrid, inhuman monsters, plotting his death, beneath the smooth mesmeric illusion of a human face?”

In Kull’s kingdom, the palace and its plots are not only metaphorically byzantine, but literally so. It is a “honeycomb,” “with worlds within worlds,” that hears aught. Behind every tapestry and wall hanging is the doppelganger palace connected by a serpentine network of secret subterranean passages more extensive than those of the Paris Opera House of The Phantom of the Opera. (Coincidentally, the Hugh Rankin cover of the August 1929 Weird Tales issue containing “The Shadow Kingdom” features Gaston Leroux’s Capt. Michel tale, “The Inn of Terror.”)

“...Ka-nu learned of this plot. His spies have pierced the inmost fastnesses of the snake priests and they brought hints of a plot. Long ago he discovered the secret passageways of the palace, and at his command I studied the map thereof and came here by night to aid you, lest you die as other kings of Valusia have died. I [Brule] came alone for the reason that to send more would have roused suspicion.”

It is the physical analogue to the “mazy” Valusian statecraft upon which an ancient enemy has woven a web of illusion and intrigue over the palace that clouds the minds of not just kings, but councilors, couriers, royal guards, and all men.

“Long ago he discovered the secret passageways of the palace…”

Only tribal rivals Kull and Brule alone stand to stop the conspiracy. Armed only with sword and spear, the two join in common cause to cut through the veil of these deceits.

“Then Brule’s lips, barely moving, formed the words: ‘The-snake-that-speaks!’”

What is this evil that lies in wait, coiled to strike and take? A poll by Public Policy Polling (March 27-30, 2013) revealed that 4% of Americans “believe that shape-shifting reptilian people control our world by taking on human form and gaining political power to manipulate our societies.” This paranoid fantasy and primal aversion is part of the power of REH’s horror, the story’s evil rooted in our primeval past.

What is this evil that lies in wait, coiled to strike and take? A poll by Public Policy Polling (March 27-30, 2013) revealed that 4% of Americans “believe that shape-shifting reptilian people control our world by taking on human form and gaining political power to manipulate our societies.” This paranoid fantasy and primal aversion is part of the power of REH’s horror, the story’s evil rooted in our primeval past.“‘Then there is further deviltry afoot.’ said Kull...”

Those who have seen the John Milius film Conan the Barbarian might remember that Thulsa Doom is a snake priest who reveals his slithery form towards the film’s end, and the serpent religion is experiencing an evil resurgence in the land as serpent temples sprout up across the Hyborian landscape. As mentioned, Doom is a character from the Kull and not Conan yarns, though not a shape-shifting serpent. One character in “Shadow,” the Pictish emissary Ka-nu, confesses to stealing “the green jewel from the Temple of the Serpent,” mirroring Conan & co.’s theft of the Eye of the Serpent from the Tower of Serpents. But the priests of the serpent god come straight from this Kull tale, with Doom a remnant of this race.

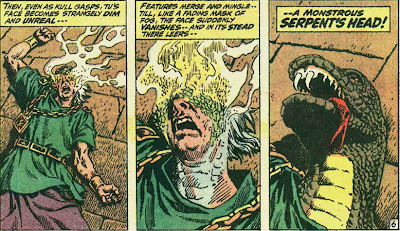

“...the face began to merge and fade, and as Kull caught his breath, his hair a-prickle, the human features vanished and there the jaws of a great snake gaped hideously, the terrible beady eyes venomous even in death.”

This treachery coming from within the kingdom is a fifth column worse than any subversive or saboteur, its infiltrators seeking to rule all mankind. Barbarians at the gate be damned, it is an invasion from within.

“‘There the true men know that among them glide the spies of the Serpent, and the men who are the Serpent’s allies – such as Kaanuub, baron of Blaal – yet no man dares seek to unmask a suspect lest vengeance befall him...’”

As Great Deceivers, they have blinded men to the historical enmity between man and serpent, the ancient archetype of evil, so that men now even build their temples.

“Yet again the fiends came after the years of forgetfulness had gone by – for man is still an ape in that he forgets what is not ever before his eyes. As priests they came; and for that men in their luxury and might had by then lost faith in the old religions and worships, the snake-men, in the guise of teachers of a new and truer cult, built a monstrous religion about the worship of the serpent god. Such is their power that it is now death to repeat the old legends of the snake-people, and people bow again to the serpent god in new form; and blind fools that they are, the great hosts of men see no connection between this power and the power men overthrew eons ago.”

King Osric laments in the film Conan the Barbarian, “Snakes in my beautiful city...Everywhere these evil towers. You alone have stood up to their gods.” As George Santayana put it, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

“Kull stood alone, his mind a-whirl. Neophytes of the mighty serpent, how many lurked among his cities? How might he tell the false from the true? Aye, how many of his trusted councilors, his generals, were men? He could be certain – of whom?”

Stephen King and S. T. Joshi may challenge REH’s originality and legacy all they like, but “The Shadow Kingdom” beats famous films dealing with almost identical premises such as The Invasion of the Body Snatchers and The Thing by decades, not to mention print stories by about half as much.

“[Kull] needed sleep, but sleep was furthest from his mind. And he would not have dared sleep if he had thought of it.”

In point of fact, REH’s tale is one of the first – if not THE first – of a long lineage of paranoid political science fiction, and it is a straight line to be drawn from “The Shadow Kingdom” (1929) to John W. Campbell, Jr.’s "Who Goes There?" (first published in the August 1938 issue of Astounding Science-Fiction) and the 1951 adaptation The Thing from Another World (including, later in 1982, John Carpenter’s The Thing), Robert A. Heinlein’s The Puppet Masters (1951), Jack Finney’s The Body Snatchers (1954) and the 1956 film version Invasion of the Body Snatchers, Richard Condon’s 1959 novel The Manchurian Candidate and the 1962 film, Jack Sholder’s The Hidden (1987), and They Live (1988) by, again, John Carpenter. “Shadow Kingdom” may well be an original of this kind of fiction.

“‘Yet the Things returned in crafty guise as men grew soft and degenerate, forgetting ancient wars. Ah, that was a grim and secret war! Among the men of the Younger Earth stole the frightful monsters of the Elder Planet, safeguarded by their horrid wisdom and mysticisms, taking all forms and shapes, doing deeds of horror secretly. No man knew who was true man and who false. No man could trust any man.’”

Appearing on many a Lovecraft book jacket and dust cover is an oft-quoted summation of his Mythos’ main theme: “All my stories, unconnected as they may be, are based on the fundamental lore or legend that this world was inhabited at one time by another race who, in practicing black magic, lost their foothold and were expelled, yet live on outside ever ready to take possession of this earth again.” While these words are widely challenged as misquote or misattribution, here in REH these words hold most terribly true.

“‘Kings have reigned as true men in Valusia,’ the Pict whispered, ‘and yet, slain in battle, have died serpents... And how can this be, Lord Kull? These kings were born of women and lived as men! This – the true kings died in secret...and priests of the Serpent reigned in their stead, no man knowing.’”

Throughout time they have been content to rule from the shadows, a shadow government if you will, shrouded by tapestries and curtains, until, “a curtain rustled...” – until now. Pull back the curtain. They’re here! The powers behind the throne have become the pretenders, hatching open rebellion and palace putsch. While fearful others dare not unmask the conspiracy, Kull’s solution cuts to the heart of the matter –

“But Kull was in his element; never before had he faced such grim foes but it mattered little; they lived, their veins held blood that could be spilt and they died when his great sword cleft their skulls or drove through their bodies. Not often did Kull forget his fighting craft in his primitive fury, but now some chain had broken in his soul, flooding his mind with a red wave of slaughter-lust.”

V

THE COMING OF BRULE AND THE PICTS

The Severins draw Brule with the straight black hair parted down the center and tanned complexion of an American Indian, an interpretation in keeping with REH’s description of the Pict as “dark, like all his race” with their “black eyes and hair,” not the typical Pict of today whose Scottish characteristics tend more toward the fair of skin and red of hair. The Indian depiction is even more appropriate as REH, in “The Hyborian Age,” describes the Picts as a people as “short, very dark, with black eyes and hair” who “built tents of hides, and crude huts,...lived mainly by the chase, since their wilds swarmed with game of all sorts, and the rivers and sea with fish, [and] dwelt in clans.” Tompkins’ intro calls them “Comanches-turned-cavalry.” Rusty Burke, in “A Short Biography of Robert E. Howard,” even identifies “the American frontier [with] the Pictish Wilderness and its borderlands...” Then, in “Marchers of Valhalla,” there is “Kelka, my blood brother, and a Pict” along with “the tom-toms of his people [that] pulsed incessantly through the hot star-flecked night.” Beyond REH’s fiction, the wild woaded Seal People of the 2011 film The Eagle remind one of Indians as much as they do Celts.

The Severins draw Brule with the straight black hair parted down the center and tanned complexion of an American Indian, an interpretation in keeping with REH’s description of the Pict as “dark, like all his race” with their “black eyes and hair,” not the typical Pict of today whose Scottish characteristics tend more toward the fair of skin and red of hair. The Indian depiction is even more appropriate as REH, in “The Hyborian Age,” describes the Picts as a people as “short, very dark, with black eyes and hair” who “built tents of hides, and crude huts,...lived mainly by the chase, since their wilds swarmed with game of all sorts, and the rivers and sea with fish, [and] dwelt in clans.” Tompkins’ intro calls them “Comanches-turned-cavalry.” Rusty Burke, in “A Short Biography of Robert E. Howard,” even identifies “the American frontier [with] the Pictish Wilderness and its borderlands...” Then, in “Marchers of Valhalla,” there is “Kelka, my blood brother, and a Pict” along with “the tom-toms of his people [that] pulsed incessantly through the hot star-flecked night.” Beyond REH’s fiction, the wild woaded Seal People of the 2011 film The Eagle remind one of Indians as much as they do Celts.If Kull of Atlantis can be seen as a frontiersman from the West and, like his proto-Celtic Atlantean descendants, the Cimmerians, “tall and powerful, with dark hair and blue or grey eyes,” then Kull and Brule teamed together make for a Lone Ranger and Tonto duo. Kull and Brule are foes-turned-friends, and as such they are the hope of the Empire as Kull works to unify the tribes into one great kingdom.

VI

AN AGE THAT TIME FORGOT

Each REH story parcels his mythology, and in this case Brule the Pict relates a history of the snake-men from when the world was young. Extinct are the goblins out of the Elder World, the bird-women, the harpies, the bat-men, the flying fiends, the wolf-people, the demons...

“‘But Kull, men were not always ruled by men!’”

Atlantis, Lemuria, the Picts, the Flood… The historical ancient world is prefigured by REH’s even more ancient world, one preceding the Hyborian age – the Pre-Cataclysmic Age (18,000 years ago), before “the Thurian Continent vanished under the waves.” If the Hyborian Age preceded our own, and this Thurian Age preceded the Hyborian, how far back does this pulp prehistory go, and how many ages are there in between? We know that as prehistory and history march on, the Atlanteans become the Cimmerians who then become the Celts...

REH’s Atlantis, a place of savagery, is not to be confused with the high civilization of Plato’s Timaeus. Before taking the throne of Valusia, Kull comes from the wilderness of Atlantis to adventure through the Seven Empires. Untamed Atlantis lies across the sea, to the West of the Empires of the Old World, and Steve Tompkins in the Kull: Exile of Atlantis introduction sees in the Kull tales “American concerns populat[ing] and animat[ing] much of the [series] (xxv).” To him, Kull is a rough-and-ready New Worlder who, not coincidentally, comes to the Old World from out of the West. REH – author of Westerns such as his Breckinridge Elkins stories – imbues his fiction with a terrain and ethos that, be it 18,000 B.C. or 10,000 B.C., sprouts from this native Texan soil. Besides clues like Picts-as-Indians, perhaps the best hint as to where we really are – or where REH’s head is – is all the talk of buffalos.

Another “American concern” the story anticipates is the Cold War paranoia (particularly evidenced in The Manchurian Candidate and Invasion of the Body Snatchers) and its sleeper agents, or more currently, terrorist sleeper cells. In Philip K. Dick’s words, “Strange how paranoia can link up with reality now and then.”

“‘Aye. Tu sleeps unknowing. These fiends can take any form they will. That is, they can, by a magic charm or the like, fling a web of sorcery about their faces, as an actor dons a mask, so that they resemble anyone they wish to.’”

Kull and Brule peel back the layers of this onion to expose a phantom menace. The two cut and slice through the veil of illusion with the metal of sword-tip and spear-point.

“Slash, thrust, thrust and swing.”

VII

LITERARY AND CLASSICAL FOREBEARS

“And so in a brooding mood Kull came to the palace ...”

“Kull sat upon his throne and gazed broodily out upon the sea of faces ...”

“So he sat and brooded in strange, mazy thought ways...”

The palace is as tapestried as Elsinore, subtly conjuring to mind the slaying of Polonius:

“There he swept aside some tapestries in a dim corner nook and, drawing Kull with him,

stepped behind them.”

“...then, sweeping back the tapestries, made the dais in a single lion-like bound.”

“...they came to a room, dusty and long unused, where moldy tapestries hung heavy. Brule drew

aside some of these and concealed the corpse behind them.”

“With a hand that shook he parted the tapestries and gazed into the room. There sat the councilors, counterparts of the men he and Brule had just slain, and upon the dais stood Kull, king of Valusia.”

“...then, sweeping back the tapestries, made the dais in a single lion-like bound.”

“Kull could hear the breeze in the other room blowing the window curtains about, and it seemed to him like the murmur of ghosts. He came with upraised dagger, walking silently...Then he advanced cautiously, apparently at a loss to understand the absence of the king. He stood before the hiding-place – and ‘Slay!’ hissed the Pict.”

In one interlude, the Melancholy Atlantean encounters the shadowy phantom of King Eallal who, with “eyes, that seemed to hold all the tortures of a million centuries,” appears in the manner the ghost of Hamlet’s father, tormented by Purgatory pain, slain by an usurper (“...that king was slain by snake-people...”).

In one interlude, the Melancholy Atlantean encounters the shadowy phantom of King Eallal who, with “eyes, that seemed to hold all the tortures of a million centuries,” appears in the manner the ghost of Hamlet’s father, tormented by Purgatory pain, slain by an usurper (“...that king was slain by snake-people...”). “The phantom came straight on...Kull shrank back as it passed them, feeling an icy breath like a breeze from the arctic snow. Straight on went the shape with slow, silent footsteps, as if the chains of all the ages were upon those vague feet, vanishing about a bend of the corridor. ‘Valka!’ muttered the Pict,...‘that was no man! That was a ghost!’ ‘That was Eallal, who reigned in Valusia a thousand years ago and who was found hideously murdered in his throne-room...

Genuine history informs REH’s pseudo-history as well, especially when the politics of Kull’s world become immediately apparent. The barbarians are not merely at Rome’s gates, they – or rather, Kull – sit upon the Throne of Kings. As a savage Atlantean, he ascends the Topaz Throne of Valusia, just as Alexander took the Greek throne in spite of his Macedonian barbarian blood. There is even an ambassador – Ka-nu, whose debauched and cynical tongue may belie an idealist – who earns Kull’s ear and gives voice to Alexander the Great’s dream of empire which would unite all the world’s tribes:

“‘And then warfare will cease, wherein there is no gain; I see a world of peace and prosperity – man loving his fellow man – the good supreme. All this can you accomplish – if you live!’”

This quote alone should give pause and challenge to authors like Norman Spinrad who in his novel The Iron Dream saw only bloodlust and Fascism in heroic fantasy literature. Ka-nu is giving voice to the romantic ideal attributed to Alexander, the foundational brotherhood of man and fatherhood of God, which courses through Western civilization’s veins from the Greek philosophers and Hebrew prophets all the way to the patristic age and the chivalric societies and later E pluribus unum republics.

“‘Go you and dream of thrones and power and kingdoms...And fortune ride with you, King Kull.’”

So Kull is not just dreaming of Empire; he is dreaming of Civilization. To do this, he must forge the Seven Empires into One, beginning with end of “world-ancient feuds,” starting with his Atlantean rivalry with Ka-nu, Brule, and the Picts...

So Kull is not just dreaming of Empire; he is dreaming of Civilization. To do this, he must forge the Seven Empires into One, beginning with end of “world-ancient feuds,” starting with his Atlantean rivalry with Ka-nu, Brule, and the Picts...“‘...such a man as I knew not existed in these degenerate days...Ah, I see long years of prosperity for the world with such a king upon the throne of Valusia.’”

In a letter to Lovecraft, REH expresses admiration for the biblical King Saul, whom he regarded as a tragic figure, and draws comparison to Kull (and Brule to his general Abner). Another Old Testament inspiration comes from Judges 12: 4-6 where the men of Gilead, in trying to root out the Ephraimite enemy in their midst, put tongue to test, those unable to pronounce “shibboleth” in the manner of the Hebrews put to the sword.

“‘Ka nama kaa lajerama!’ ... For that phrase has come secretly down the grim and bloody eons, since when, uncounted centuries ago, those words were watchwords for the race of men who battled with the grisly beings of the Elder Universe. And men used those words which I spoke to you as a sign and symbol, for as I said, none but a true man can repeat them. For none but a real man of men may speak them, whose jaws and mouth are shaped different from any other creature. Their meaning has been forgotten but not the words themselves.”

Kull is prone to falling into dark reveries, though they are not murderous moods as are Saul’s (or for that matter, the drunken rages of Alexander), but instead musings more akin to a certain melancholy Dane. In “By This Axe I Rule!,” Kull says of his court poet Ridondo –

“He hates me, yet I would have his friendship. His songs are mightier than my sceptre, for time and again he has near torn the heart from my breast when he chose to sing for me. I will die and be forgotten, his songs will live forever...”

– recalling Saul whose savage breast was soothed only by the harp-melodies of the psalm-singer David. Saul rewards the future king David’s kindnesses by hurling spears at him, but Kull spares Ridondo from death, despite his treasonous verses.

In another possible influence, St. Patrick legendarily cast out snakes from the Hibernian realm, and from the pre-Hyborian lands Kull vows to drive the snake-men with sword and fury.

“‘...may the serpent-men of the world beware of Kull of Valusia.’”

REH, intensely proud of his Irish heritage, would have been fully aware of Patrick’s story. The Texan’s fascination with things Celtic is why his fiction is populated with proto- and pseudo-Celt tribes from Picts to Cimmerians, and many of his characters share this ancestry (Kull, Brule, Conan, Bran Mak Morn, and Cormac Fitzgeoffrey, to name some). The Ballad of the White Horse, by one more favorite of REH’s, G. K. Chesterton, served as yet another inspiration to his fiction. The Ballad is an epic poem about the tribes of the British Isles and their unification under King Alfred against heathen Scandinavian invaders.

REH’s classical allusions are why Patrice Louinet, in his Atlantean Genesis essay, questions terms like “Heroic Fantasy,” “Epic Fantasy,” and “Sword and Sorcery,” dismissing them as “unsatisfying” and “reductive,” and rightly wonders if anyone would think to label Hamlet “sword-and-sorcery” because of a ghostly visitation. “Shadow Kingdom” is routinely credited with creating what is called the “sword-and-sorcery” genre, but whole anthologies have been compiled with past fantasy stories which may qualify as “sword-and-sorcery,” Douglas A. Anderson’s Tales Before Tolkien: The Roots of Modern Fantasy and Tales Before Narnia: The Roots of Modern Fantasy and Science Fiction (like the most recent, and best, REH collections, from Del Rey) chief among them. Steve Tompkins, in the Del Rey introduction to Kull: Exile of Atlantis, writes that “It is not quite accurate to label ‘The Shadow Kingdom’...the original sword-and-sorcery story,” claiming that “To do so is to overlook an earlier masterpiece, Lord Dunsany’s 1910 ‘The Fortress Unvaquishable, Save for Sacnoth,’ in which a swordsman invades the hellish, dragon-guarded stronghold of an archmage.” The excellent anthology series Echoes of Valor traces the genre back even further to Homer.

None of this is to diminish REH’s historic contribution as a founding father of modern fantasy literature – “Shadow” predates even J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis, and REH just might be the first American to pen fantasy of this kind – but rather a reminder how literature of this type almost defies these hair-splitting, on-the-nose classifications. Wisely the editors of Kull the Conqueror #2 hedge their bets by using the phrase “...more-or-less accurate label of ‘sword-and-sorcery’” to describe “Shadow’s” contribution to the genre.

There is probably more to be learned about “Shadow” and its classical allusions than we will ever know. REH wrote Harold Preece (October 20, 1928) that “All my views on the matter [Atlantis, etc.] I included in a long letter to the editor to whom I sold a tale entitled ‘The Shadow Kingdom,’ which I expect will be published as a foreword to that story – if ever. This tale I wove about a mythical antediluvian empire, a contemporary of Atlantis.” Unfortunately for posterity, that letter is as lost as Khitai and all the mythic places and Ages REH wrote about during his short life. One wonders what light it might have shed on this unsung seminal work.

VIII

THE END...OR IS IT?

“‘And let those rotting skeletons lie there forever as a sign of the dying might of the Serpent. Here I swear that I shall hunt the serpent-men from land to land, from sea to sea, giving no rest until all be slain, that good triumph and the power of Hell be broken. This thing I swear – I – Kull – king – of – Valusia.’”

We do not know if Kull was triumphant in his crusade to vanquish the snake-things from the face of the lands as they never surface in another Kull tale. They are mentioned in Lovecraft’s short story “The Haunter of the Dark” (Weird Tales, December 1936) – “the serpent-men of Valusia” – but as ancient history. Having “lost their foothold,” we do not know if they “live on outside ever ready to take possession of this earth again.” There may be no more snake-men in the too-close-for-comfort twentieth century of Lovecraft's America but there are Deep Ones and other “grisly beings of the Elder Universe,” as well as assorted human agents and worshippers and other allies of these hidden things, so it is not a far cry to say, at least in the pulp fiction universe, “They’re here already! You’re next! You’re next!” For all we know, they are among us now, at least somewhere in the yellowed pages of some obscure story magazine of yore, waiting to be uncovered by some dedicated pulp reader. And if they are, they may owe it all to REH.

END

Gilbert, thanks for this very detailed look at the Kull story! I was especially interested in the parallels to ancient near-eastern sources. This is clearly a subject close to your heart.

ReplyDeleteGilbert,

ReplyDeleteThanks for the in-depth scholarly article.

Have to agree, what an exhaustive work of scholarship. Magnifico!

ReplyDeleteSuch scholarship--and from such a self-effacing source. ("Well, I'm no expert, but..." Pshaw!) It's a good thing "These essays will appear on an irregular basis," or I might never have time to read anything else, and I mean that in the nicest possible way. My only quibble, and it's more of an editorial one, is that as posted, the piece does not make it immediately clear which comic(s) it is analyzing so impressively. But what is "woaded"?

ReplyDeleteFascinating for a guy like me, who knows the characters through neither their pulp nor their Marvel incarnations, to learn that Kull had the edge over Conan among such REH enthusiasts as Bloch, and that his depiction got a thumbs-up from several of those in Howard's circle. But scary to think that even a statistically significant minority of Americans believe we're controlled by snake-people.

Of course, this being Gilbo, it all comes back to Milius!