by Pulp Practitioner and Professor

Gilbert Colon

Doc Savage Vol 2 #1

August 1975

Marv Wolfman, Editor

Archie Goodwin, Consulting Editor

John Warner, Assistant Editor

Lenny Grow, Production

Barbara Altman & Nora Maclin, Designs

Michele Wolfman, Photo Editor

“A Return to Greatness!” for pulp superhero Doc Savage in this “1st Issue Spectacular,” this time in magazine form. In contrast to the Marvel comics running from 1972-1974 which credited Kenneth Robeson, this magazine premiere uses Robeson’s real name for the first time, declaratively dedicating the issue “to LESTER DENT – the man who began it all!”

In addition to “a power-packed 53-page sensation” with the wonderfully pulpy title “The Doom On Thunder Isle!” (called “Doom on Thunder Island” on the contents page), there are 10 pages of – as boldly exclaimed on the cover – “A Doc Savage Movie Exclusive: George Pal Speaks!” (The Ron Ely movie-inspired cover art, incidentally, is “by ROGER KASTEL from the Warner Brothers presentation of George Pal’s production of DOC SAVAGE, staring [sic] Ron Ely.”)

Unlike in Marvel’s earlier comic series with 20 pages devoted to a story, more pages here means more space to introduce and juggle its six characters (Doc and the Amazing Five), and to Moench’s credit he keeps the Thirties setting that they were almost tempted to abandon back in 1972.

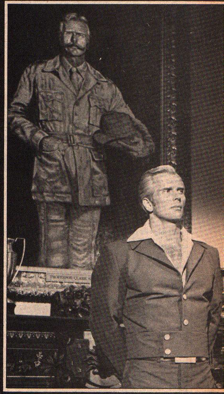

Setting the tone for the magazine is a frontispiece, “The Two Faces of Doc Savage,” with Doc Savage: The Man of Bronze star himself Ron Ely posing next to a framed James Bama portrait of the Man of Bronze from Doc Savage: The Arch Enemy of Evil (the abandoned sequel to George Pal’s 1975 movie). While Pal’s film sticks more closely to the original pulp cover art interpretation of Doc, Buscema and DeZuniga’s art for “The Doom on Thunder Isle!” continues the almost definitively Bama-esque look established at Marvel by their previous comic series.

A Personal Vision by Marv Wolfman

Wolfman explains that Doc Savage’s “comics career has been less than world-shaking,” relating how “In the 1940’s, Doc appeared in the back of ‘The Shadow’ comic,” eventually “Graduating into his own book [which] lasted just a few short years before being once again relegated to the Shadow’s filler pages.” Marvel’s own comic history receives a brief sketch: “A few years ago, Marvel published eight issues of a brand-new Doc Savage comic… Once again, Doc didn’t fare all that well. Perhaps the time, or even the approach was wrong. It’s hard to say.” (At the time of this debut magazine, “the first two [comics] have been reprinted” to tie in with both Doc’s return to Marvel’s pages and the Pal film.) Wolfman “give[s] a personal thanks to Bob Weinberg, publisher of Pulp magazine for his advice and assistance in arranging articles.” The “Editorial in Bronze” ends with a pitch for those “in fandom interested in Doc and other thirties adventure heroes” to “send a self-addressed, stamped envelope to Bob for info about his mag.” (Sadly Pulp ceased publication in 1981, its history all-too-briefly sketched in Marvin Lachman’s The Heirs of Anthony Boucher.)

“The Doom on Thunder Isle!”

Writer: Doug Moench

Artists: John Buscema & Tony DeZuniga

Billed as not merely a comic, but a “senses-shattering novel by Doug Moench, John Buscema, and Tony DeZuniga!,” the story is “based on the characters created by KENNETH ROBESON (Lester Dent) as published by BANTAM BOOKS.” In other words, not upon any of the 181 novels (159 of them from Dent’s pen). The contents page sums it up nice and neatly: “Doc and his Amazing Five battle the bizarre menace called ‘The Silver Ziggurat,’ only to find themselves facing—the deadly MANIMALS!” In between…:

A Manhattan skyscraper is destroyed by a mysterious super-criminal, as in Doc Savage #3 (“Death in Silver!”). His criminal gang is costumed a lot like the Silver Death’s-Heads league from both Dent’s original novel Death in Silver and Marvel’s adaptation, and while they might not have the visage of an SS silver death’s head skull like those stories’ “silver men,” their jet-black outfits do sport silver lightning bolts recalling Hitler’s SS. (This is the Thirties, after all!) The mastermind, their leader, is even called “the Silver Ziggurat,” suggesting both the pyramid of the first Doc Savage novel – its architecture as unusual as the Ziggurat’s lair – and the “silver devils” of Death in Silver. (Besides being the word for a kind of stepped pyramid, “ziggurat” is also “the Art Deco term for lightning bolt insignia--.”) When the baddies are bested by the Man of Bronze and his Iron Men, they commit suicide rather than face capture, combining the poison capsule demise of the silver-suited thief from Doc Savage #3 (“Death in Silver!”) with the self-defenestration of the Quetzalcoatl-worshipping sharpshooter in Doc Savage #1 (“Doc Savage, the Man of Bronze!”). The roll of paper hidden inside the hollow Chiparus statute is like the map inside the cube the Bronze Man deciphers from Doc Savage #8 (“Werewolf’s Lair!”). Doc and his team reach the Doctor Moreau-ish island of the title to find a race of “Manimals,” the result of mad-scientist experimentation like “the men-monsters” of Doc Savage #5 (“The Monsters!”) and #6 (“Where Giants Walk!”) who also dwell on a “hidden island stronghold.”

A Manhattan skyscraper is destroyed by a mysterious super-criminal, as in Doc Savage #3 (“Death in Silver!”). His criminal gang is costumed a lot like the Silver Death’s-Heads league from both Dent’s original novel Death in Silver and Marvel’s adaptation, and while they might not have the visage of an SS silver death’s head skull like those stories’ “silver men,” their jet-black outfits do sport silver lightning bolts recalling Hitler’s SS. (This is the Thirties, after all!) The mastermind, their leader, is even called “the Silver Ziggurat,” suggesting both the pyramid of the first Doc Savage novel – its architecture as unusual as the Ziggurat’s lair – and the “silver devils” of Death in Silver. (Besides being the word for a kind of stepped pyramid, “ziggurat” is also “the Art Deco term for lightning bolt insignia--.”) When the baddies are bested by the Man of Bronze and his Iron Men, they commit suicide rather than face capture, combining the poison capsule demise of the silver-suited thief from Doc Savage #3 (“Death in Silver!”) with the self-defenestration of the Quetzalcoatl-worshipping sharpshooter in Doc Savage #1 (“Doc Savage, the Man of Bronze!”). The roll of paper hidden inside the hollow Chiparus statute is like the map inside the cube the Bronze Man deciphers from Doc Savage #8 (“Werewolf’s Lair!”). Doc and his team reach the Doctor Moreau-ish island of the title to find a race of “Manimals,” the result of mad-scientist experimentation like “the men-monsters” of Doc Savage #5 (“The Monsters!”) and #6 (“Where Giants Walk!”) who also dwell on a “hidden island stronghold.”  A letter published in the magazine Doc Savage #3 asks, “Shouldn’t the Manimals have been brought into the story earlier…?” Marvel reports that “Doug [Moench] says No…” because his “motives were in complete accordance with Lester Dent’s highly formularized plotting…blueprint-outline (reputedly tacked to the wall above Dent’s typewriter) [which] dictated that surprise should follow surprise almost as quickly as event followed event; just as the reader thinks he knows what’s happening, you pull a whammy of startling magnitude. And the biggest whammy was always saved for the climax. Therefore, doesn’t the Manimal sequence (and final revelation of the Silver Ziggurat’s true identity) fit the bill as an extremely Dent-like plotting device…?”

A letter published in the magazine Doc Savage #3 asks, “Shouldn’t the Manimals have been brought into the story earlier…?” Marvel reports that “Doug [Moench] says No…” because his “motives were in complete accordance with Lester Dent’s highly formularized plotting…blueprint-outline (reputedly tacked to the wall above Dent’s typewriter) [which] dictated that surprise should follow surprise almost as quickly as event followed event; just as the reader thinks he knows what’s happening, you pull a whammy of startling magnitude. And the biggest whammy was always saved for the climax. Therefore, doesn’t the Manimal sequence (and final revelation of the Silver Ziggurat’s true identity) fit the bill as an extremely Dent-like plotting device…?”

The Manimals are imprisoned in a high-voltage fence similar to the electrified net from the comic Doc Savage #5. The villain behind it all, “the Great Silver Zigurat!! [sic],” is unmasked as Thomas J. Bolt, fiancé to the sister of the architect who built the obliterated skyscrapers, the same architect previously under suspicion (until they found him being turned into a beast-man by the Silver Ziggurat). The big finale sees the Silver Ziggurat’s zeppelin crashing and burning, appropriately enough, in a Hindenburg conflagration.

Moench pulls out all the stops, hauling out Doc’s roadster, the autogyro, the Helldiver submarine – all featured in the previous color comic series – and even upping the ante with the first and only Marvel appearance of Doc’s zeppelin, the Amberjack. While Doc and his crew match the codebreakers of The Imitation Game (at least in these comic pages), Moench devotes an undue amount of time to the cracking of cryptograms, slowing things down to a crawl in spots except for those enamored with brainteasers.

All this switching of Manimals from man-monsters and Silver Death’s-Heads to Silver Ziggurat gives you an idea of how similar this material is to previous Doc Savage stories. This turns out to be a double-edged sword, in many ways. On the one hand it demonstrates a real knowledgeability and feel for the material – Moench definitely has the formula nailed – but also an inability to bring anything original to what is supposed to be a brand-new story. The latter is not necessarily a liability, but it does beg the question: Why not adapt one of the other 181 novels? Or why not at least borrow scenes from the scores and scores of novels Marvel never got around to adapting? (Though Dent wrote almost all the original novels, Frank Herbert contributed a short story well before his Dune days, so it might have been fun to see something like this adapted.) Wolfman, in his editorial, is right though that the story by “Meonch [sic]” does have “the flavor and excitement of Dent’s early works,” just as it is true that “Buscema’s incredible story-telling adds exactly the right feel and mood to Doc,” and this is no small accomplishment, especially in light of George Pal’s tongue-in-cheek film adaptation covered in this same issue. In that spirit, a man being questioned by Doc on page 23 is “ZRAKT” by the lightning death-ray right before divulging information, which is exactly how the supervillain The Lightning dispatches someone in the old Republic serial The Fighting Devil Dogs (1938). Whatever Moench’s missteps, he captures the tone of 1930s pulp adventure, so perhaps Pal should have gotten him on board.

All this switching of Manimals from man-monsters and Silver Death’s-Heads to Silver Ziggurat gives you an idea of how similar this material is to previous Doc Savage stories. This turns out to be a double-edged sword, in many ways. On the one hand it demonstrates a real knowledgeability and feel for the material – Moench definitely has the formula nailed – but also an inability to bring anything original to what is supposed to be a brand-new story. The latter is not necessarily a liability, but it does beg the question: Why not adapt one of the other 181 novels? Or why not at least borrow scenes from the scores and scores of novels Marvel never got around to adapting? (Though Dent wrote almost all the original novels, Frank Herbert contributed a short story well before his Dune days, so it might have been fun to see something like this adapted.) Wolfman, in his editorial, is right though that the story by “Meonch [sic]” does have “the flavor and excitement of Dent’s early works,” just as it is true that “Buscema’s incredible story-telling adds exactly the right feel and mood to Doc,” and this is no small accomplishment, especially in light of George Pal’s tongue-in-cheek film adaptation covered in this same issue. In that spirit, a man being questioned by Doc on page 23 is “ZRAKT” by the lightning death-ray right before divulging information, which is exactly how the supervillain The Lightning dispatches someone in the old Republic serial The Fighting Devil Dogs (1938). Whatever Moench’s missteps, he captures the tone of 1930s pulp adventure, so perhaps Pal should have gotten him on board.

An interview with George Pal, writer and producer of the film,

DOC SAVAGE: THE MAN OF BRONZE

DOC SAVAGE: THE MAN OF BRONZE

Proving in more than one sense of the phrase that we are living in “the Marvel Age of Behind-The-Scenes-Info,” this nonfiction section, rich in black-and-white stills from photo editor Michele Wolfman, is composed of two separate “in-depth interview[s] with the greatest science-fiction director of them all – and the man who gave life to the greatest pulp crime-fighter ever – George Pal.” Throughout both segments, Pal consistently says almost all the right things, but what ended up on the screen feels at odds with his words in these two interviews.

GEORGE PAL: THE MAN WHO SHOT DOC SAVAGE!

PART 1—by Chris Claremont/New York

Pal opens by articulating his beginnings, first graduating as an architect in Budapest, then realizing “there was no building in Hungary, whatsoever,” which led him “to make animated cartoons.” He “drew pretty well…and…travelled around in Europe making animated cartoons.” Frustrated with “flat animation,” he went in “search for the third dimension in animation” and “invented the process called ‘Puppetoons.’” In the meanwhile he made “advertising pictures…up to five or six minutes long,” a road that ultimately led him to “pictures like Destination Moon, When Worlds Collide and War of the Worlds.” During this time “we made ‘disaster pictures’ just like the ones…in vogue now…like The Towering Inferno, Earthquake, Airport and Hindenburg.” In other words, he was Irwin Allen before Irwin Allen. At the time of this interview, he had “the biggest disaster in the oven” based on When Worlds Collide co-author Philip Wylie’s novel The Disappearance, as well as a sequel to his 1960 film The Time Machine called The Time Traveller and a sequel to his Doc Savage film, none of which ever got off the ground. (Interestingly, Richard A. Lupoff cited the opinions of pulp historians who claim that Wylie’s 1932 novel The Savage Gentleman served as a precursor to Lester Dent’s hero.)

Pal decries the fantasy label put upon his Destination Moon because “we…had the best advisors all along the line: Robert Heinlein and Jeffrey Bannister, the painter, Dr. Sewicky and Willy Ley…and we even had Werner von Braun…” He relates his interest in the Doc Savage project originating when he “bump[ed] into Ray Bradbury” browsing in a bookstore and being attracted to Bantam’s “beautifully drawn covers…” He also “noticed that at the beginning of the month there were lots of Doc Savage books and then by the end…practically all of those paperbacks had disappeared…” which he obviously took as a good sign for box office. This led him to “read a few [and recognize] that this is wonderful motion picture material.” Then after competing with other producers on the rights bidding, Pal recalls being humbled when “Mrs. Dent—the widow of the series’ author, Lester Dent—selected me…”

Pal decries the fantasy label put upon his Destination Moon because “we…had the best advisors all along the line: Robert Heinlein and Jeffrey Bannister, the painter, Dr. Sewicky and Willy Ley…and we even had Werner von Braun…” He relates his interest in the Doc Savage project originating when he “bump[ed] into Ray Bradbury” browsing in a bookstore and being attracted to Bantam’s “beautifully drawn covers…” He also “noticed that at the beginning of the month there were lots of Doc Savage books and then by the end…practically all of those paperbacks had disappeared…” which he obviously took as a good sign for box office. This led him to “read a few [and recognize] that this is wonderful motion picture material.” Then after competing with other producers on the rights bidding, Pal recalls being humbled when “Mrs. Dent—the widow of the series’ author, Lester Dent—selected me…”

Pal, like Marvel, was “tempted to bring the series up to date,” but conceded that “The characters don’t belong to today; they’re nineteen-thirties characters and that means they’re charming and interesting…” Almost anticipating criticism, however, Pal defensively adds that “if they begin to look ‘Campy’ that’s not because we tried to make it campy but because the material itself, if you want to use that word, [is] campy….” Then, when Marvel interviewer Claremont balks at the word, Pal claims to be “just playing it straight….” in the film. (It seems clear that from the beginning, something about the tone, both in the novels and the film, was still elusive and unresolved in Pal’s mind.)

To his credit, Pal does say that “what Doc Savage stands for is wonderful. I compare it with…Patton…” Specifically, he compares “George C. Scott’s delivery of that keynote speech in Patton” to the Man of Bronze “when he delivers his code.” And rightly so. “Nobody can forget it—in front of the American flag, the huge American flag, Patton delivers a speech with which you don’t necessarily agree, or probably disagree, but you admire the man for believing in that principal of his.” This Pal is probably obligated to say in order to fill theater seats in a decade rife with anti-American sentiment. After all, comparing Doc’s Code with Patton’s speech, and calling “what Doc Savage stands for” as “wonderful,” suggests admiration on some level. And, Pal adds, “The Doc Savage speech is wonderful” – that word again – “it’s beautiful; and some people smile—they’re amused by the man—some people take it seriously.” That they do.

Claremont worries about adaptations because “one hopes—one always wants these films—well, you know the films made of Edgar Rice Burroughs’ novels, especially a lot of the Tarzan films, are never as good as the books.” (Coincidentally, or perhaps not, Ely starred as Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Lord of the Jungle in the 1966 series Tarzan that aired on NBC.) He zeroes in on the fact that they “lack the scope and the imagination and the fun” that he speculates stems from “the feeling that the people who made the films were laughing at what they were doing while they were doing it.” There are times – too many times – in Pal’s film that you will think that Claremont’s expressed doubts, despite his enthusiasm for Pal’s upcoming Doc Savage, turn out to be almost prescient. Nevertheless, Pal steadfastly insists “That’s one thing we don’t do” and that to make a film like this, you have to “believe and don’t consider the people you make it for as twelve years old….” It is unclear from the final product just who the finished film is for.

Claremont worries about adaptations because “one hopes—one always wants these films—well, you know the films made of Edgar Rice Burroughs’ novels, especially a lot of the Tarzan films, are never as good as the books.” (Coincidentally, or perhaps not, Ely starred as Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Lord of the Jungle in the 1966 series Tarzan that aired on NBC.) He zeroes in on the fact that they “lack the scope and the imagination and the fun” that he speculates stems from “the feeling that the people who made the films were laughing at what they were doing while they were doing it.” There are times – too many times – in Pal’s film that you will think that Claremont’s expressed doubts, despite his enthusiasm for Pal’s upcoming Doc Savage, turn out to be almost prescient. Nevertheless, Pal steadfastly insists “That’s one thing we don’t do” and that to make a film like this, you have to “believe and don’t consider the people you make it for as twelve years old….” It is unclear from the final product just who the finished film is for.

Much later in the interview, Pal confesses feeling “it was important not to direct,” so he handed the reins over to “my good friend, Michael Anderson [because] we always wanted to do a picture together…” Anderson, whose genre credits include 1984 (1956), The Martian Chronicles (1980), and 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1997) – and who directed Logan’s Run (1976), a project which Pal was once attached to in 1968 – was slated for the Savage sequel too. It is difficult to know how much of the blame for Doc Savage: The Man of Bronze’s tonal dissonance can be laid at Pal’s feet versus Anderson’s, though they both must share in it. What should have been Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981) ended up more like Mike Hodges’ Flash Gordon (1980), killing any chances for a franchise.

This brings Pal to the second Man of Bronze film, which would have benefited from the “opportunity to include more action and more excitement” because they did not have to “establish Doc save…the Amazing Five…[etc.].” Obviously it was ultimately unmade, except for some principal photography according to some sources which cite Death in Silver as the novel which would have formed its basis. Pal goes further to say that this “screenplay [was] based on several novels” but failed to introduce the core characters and other elements. This “original screenplay [went back] on the shelf” because “you have to make The Man of Bronze first before you do any of the other stories.” The only reason they didn’t originally go this route was because they felt the introductions would come at the expense of the action. Later he says even a third one is planned for the future. One sequel “is placed mainly in…old New York during the prohibition era, [with] gangsters…the Walter Winchell era. And the third one, which Philip Jose [sic] Farmer is writing, plays in…the Morocco of Casablanca [with] a Peter Lorre- [and] a Claude Rains-type of character.” Farmer, who wrote a Doc Savage novel of his own as well as a famous fictional biography, would almost have certainly caused controversy among Man of Bronze fans who may well have objected to the revisionism in his pastiche work. Marvel pitches the idea of a Man of Bronze television series, but Pal envisions “Doc Savage as a series of pictures…like…Bond…”

This brings Pal to the second Man of Bronze film, which would have benefited from the “opportunity to include more action and more excitement” because they did not have to “establish Doc save…the Amazing Five…[etc.].” Obviously it was ultimately unmade, except for some principal photography according to some sources which cite Death in Silver as the novel which would have formed its basis. Pal goes further to say that this “screenplay [was] based on several novels” but failed to introduce the core characters and other elements. This “original screenplay [went back] on the shelf” because “you have to make The Man of Bronze first before you do any of the other stories.” The only reason they didn’t originally go this route was because they felt the introductions would come at the expense of the action. Later he says even a third one is planned for the future. One sequel “is placed mainly in…old New York during the prohibition era, [with] gangsters…the Walter Winchell era. And the third one, which Philip Jose [sic] Farmer is writing, plays in…the Morocco of Casablanca [with] a Peter Lorre- [and] a Claude Rains-type of character.” Farmer, who wrote a Doc Savage novel of his own as well as a famous fictional biography, would almost have certainly caused controversy among Man of Bronze fans who may well have objected to the revisionism in his pastiche work. Marvel pitches the idea of a Man of Bronze television series, but Pal envisions “Doc Savage as a series of pictures…like…Bond…”

When Claremont asks Pal if the controversial “‘corrective’ surgery” (with which Doc, in the novels, turns villains into “decent members of society”) deserved “any kind of editorial judgment,” the movie producer insists no because “Savage’s process” – which he describes as “operation or …acupuncture” – “is very much in the thinking of today’s crime prevention…” Pal is certain that “people just accept it beautifully,” eliciting a one word comment from his interviewer: “Really?” In the post-Miranda era of crime-fighting, Pal might have again misjudged the populace, though maybe he was counting on the demographic who went to see Death Wish, the Dirty Harry films, Walking Tall, Mad Max, and all the other films reacting to the soft-on-crime Seventies.

About pulp as a genre, Pal certainly grasps its appeal, saying about the magazines and stories of that era: “I love them [because] they’re very much entertainment. They take you away from the gruesomeness of today’s life, you know; you really can escape and get into another world, a world you can really enjoy.” But the man who made his name making extraordinary escapism – from tom thumb to The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm to 7 Faces of Dr. Lao – seemed unable to translate pulp to his medium of choice, the big screen, at least not without a twinkle-eyed wink and a nod.

Claremont quotes the film’s press release “about the character of Doc Savage[:] ‘He’s a big, square Joe with the body of Charles Atlas, the brain of Thomas Edison and the implacable innocence of Mickey Mouse.” This may be part of the problem with his vision for the film as that summation is quite a step down from Dent’s own: “I took Sherlock Holmes with his deducting ability, Tarzan of the Apes with his towering physique and muscular ability, Craig Kennedy with his scientific knowledge, and Abraham Lincoln with his Christliness.” Edison and Atlas are perfectly acceptable inspirations, but with all due deference to Mickey Mouse, there is not quite the same seriousness of purpose in the press release’s vision. Claremont expresses concern that “audiences today might feel, ‘We’re too sophisticated for that;’ or that people might laugh at the character?” An undeterred Pal winds up saying how it will be “a wonderful feeling to see a real honest-to-goodness true hero,” never allowing that “honest-to-goodness true hero” depictions can vary and range from Adam West’s campy Batman to the more earnest but breezy Christopher Reeve Superman films to come, not to mention different shadings of dark like Tim Burton’s Batman films and Christopher Nolan’s Dark Knight trilogy. Still, Claremont holds out hope that Pal’s film “will spark a trend [and] that perhaps…there will be a Destructor series, or Shadow series…” Pal, overbrimming with confidence, replies, “I wouldn’t be surprised.”

Pal concludes that “we shot a lot of muscle men but once we had made the test with Ron Ely there was no contest. He was it. He’s Doc Savage.” (No wonder this magazine’s bodybuilding ads, particularly the full-page Charles Atlas fitness spread in next month’s, and if you need a Doc workout, there are plenty of Buscema- and DeZuniga-illustrated training scenes in these pages to guide your own exercises!) Had Atlas been alive at the time of the film’s casting, Pal would have no doubt even auditioned him – Atlas certainly dresses the part of the Doc of the pulps in the pages of Physical Culture magazine (October 1921).

GEORGE PAL: THE MAN WHO SHOT DOC SAVAGE!

PART 2—by Jim Harmon/Hollywood

The second part would have done better in another issue as it covers much of the same material from the first interview. We do learn, from interviewer Harmon, that “Destination Moon…had an organized ‘fan club’ following.” Pal relates an ingenious special effects solution they came up with for Destination Moon. To “make a false perspective” on their moon stage “so that figures would appear to be in the distance,” they “us[ed] normal figures in the foreground and midgets in the background.”

One thing Pal would like to do again would be to film Puppetoons, “but it is financially impossible.” The main reason is that “It cost plenty…back then and today it is prohibitive” considering the fact that “theaters don’t pay enough for any short—cartoons, Puppetoons, anything.”

For Doc Savage: The Man of Bronze, Pal “made part of the deal with” Lester Dent’s wife Norma and consulted with her. Mrs. Dent helped “clear the rights to all these one hundred eighty-one stories,” and “She and the other owner, Conde-Nast (successors to Street & Smith), selected me among three would-be producers.” The grateful Pal is “happy to say Mrs. Dent will have a percentage of all these pictures.”

As for the screenplay, it “was written by Joe Morheim, and by myself…This is the first time I have taken screen credit, but I worked hard on this.” Morheim co-wrote the novel Time Machine II with Pal – published six years later, in 1981, one year after Pal’s death – which was based on the never-made sequel The Time Traveller.

Pal’s interest in pulp extends to the Doc Savage creator himself. He looks forward to “a book about Mr. Dent coming out,” presumably The Man Behind Doc Savage: A Tribute to Lester Dent by Robert Weinberg. “I’m very curious about what kind of a man he was. I have a feeling he was a very happy man. He was out going around the world, treasure-hunting for sunken gold. He must have lived.” Agreeing, Harmon calls Doc Dent’s “egoprojection.”

Pal keeps active himself. When Harmon notes that “you have a metal bar braced in the doorway to your inner office,” he explains, “I do pull-ups” and “used to work in the gym on rings and bars.” The interviewer finds it “appropriate that the producer of Doc Savage does exercise” since “Doc was always a great believer in working out.”

Knowing what a shrewd businessman Pal is, Harmon broaches the topic of “promotionals and merchandising.” Pal cites “a record album in the manner of an old drama,” calling it “one of the more interesting projects.” In fact, this album “may serve as the pilot for a regular Doc Savage radio show.” Pal will “sometimes hear this new CBS Radio Mystery Theatre at night,” so he knows “radio programs are coming back.” The interviewer asks if he could “find any of the old original Doc Savage radio shows of the thirties,” but Pal could not. “Some scripts for the old show were found,” Pal hurries to add, and “these will be the basis for the record album.” In addition, “we hope to clear the rights for the Doc Savage theme we use in the picture, and the lyrics, for the record” and is hoping to recruit “Ron Ely, to try to get him to play Doc” since “Ron says it sound like fun…” The interviewer “suppose[s] the other members of the record cast will be old-timers experienced in radio,” and Pal confirms that “Most of the people from the picture are,” noting that “The fellow who plays Ham is an experienced radio actor.”

Knowing what a shrewd businessman Pal is, Harmon broaches the topic of “promotionals and merchandising.” Pal cites “a record album in the manner of an old drama,” calling it “one of the more interesting projects.” In fact, this album “may serve as the pilot for a regular Doc Savage radio show.” Pal will “sometimes hear this new CBS Radio Mystery Theatre at night,” so he knows “radio programs are coming back.” The interviewer asks if he could “find any of the old original Doc Savage radio shows of the thirties,” but Pal could not. “Some scripts for the old show were found,” Pal hurries to add, and “these will be the basis for the record album.” In addition, “we hope to clear the rights for the Doc Savage theme we use in the picture, and the lyrics, for the record” and is hoping to recruit “Ron Ely, to try to get him to play Doc” since “Ron says it sound like fun…” The interviewer “suppose[s] the other members of the record cast will be old-timers experienced in radio,” and Pal confirms that “Most of the people from the picture are,” noting that “The fellow who plays Ham is an experienced radio actor.”

Looking back through the lens of history, there were some movie tie-in products like a 7” statuette of Ely as the Man of Bronze and a jigsaw puzzle, plus the usual movie posters and lobby cards floating around, but collectors will have to weigh in if any of the ambitious merchandise, previously listed, ever even went into production. Of course in the absence of movie memorabilia, these Marvel magazines serve quite well. This first issue with Ely on its cover qualifies as a tie-in, and next issue scores an interview with Ely himself. Still it is odd that no novel reissue of Dent’s first novel with movie art ever found its way to print, nor a record of the film’s score so beloved by Pal.

That brings us to the film music. “We felt that the perfect music…was a stirring march. Who wrote the best marches? John Philip Sousa! It just somehow fits perfectly [and] Don Black who got the Academy Award for lyrics on Born Free, and got several nominations for Goldfinger and others, wrote the lyrics for our Doc Savage March. Beautiful lyrics, in the spirit of the ‘Code’! We have a male choir singing it, and it is very blustering—thrilling!” For the actual score, “Frank DeVol adapted the music,” but “Ninety per cent [sic] of the score is based on Sousa. Even our love theme is Sousa—slowed down, played schmaltzy with violins and harps.” At no point does Pal address the inclusion of the comedic “La Cucaracha” sequence which no one could argue with a straight face belongs in a straight adaptation.

Harmon assumes that Pal “must have had difficulties in finding the location and machines of the ’30s” for the film,” and all Pal says is that “This is a very expensive-looking production,” confirming that the plane is real and not a prop. There is, too, the gadgetry. Doc “even has an answerphone—but in the period of the thirties.” In Claremont’s part one interview preceding Harmon’s, Pal revealed that location shooting included Grand Junction for the desert, Colorado for the Fortress of Solitude in the Artic, but for “the New York of the 1930’s” it had to be “the studio back lot…”

There is no truth to the rumor that Pal and Ely had a bad relationship during filming, with Pal saying that “Ron is looking forward to the next picture—Doc Savage, Arch Enemy of Evil. For this movie, they followed the first book but “made some cinematic changes [which] I’m sure the original author would have approved.” One for instance offered is the great geyser-like pool of liquid gold in the South American pyramid instead of just simply gold as in the novel. “It will be a very spectacular eruption…very cinematic.”

Harmon inquires whether Doc’s cousin Patricia Savage will ever star, and Pal thinks it will “be better to bring her on later in the series.” Then the interviewer interjects his own suggestion for a good Doc Savage movie, The Land of Terror, and Pal does not miss a beat in proving his familiarity with Dent’s novels (which ought to be the case since he probably paid in liquid gold for the rights to 181 stories!). Quickly recognizing the title, Pal says not “for awhile [sic] [as] it involves prehistoric monsters” and “that kind of picture, you’ve seen before.” Yet even though Pal says “It would cheapen the concept,” he ends up conceding “We do intend to do the prehistoric story eventually.” It sounds like Pal, for better or for worse, wanted to adapt a lot of Doc. The first step for now is “get[ting] people to believe in Doc Savage.” After that set-up, subsequent installments would take Doc to “the Orient” and beyond. “Eventually, we will go further away from the world we know. Even, I imagine, into outer space.”

Again we return to the question: “Do you think,” asks Harmon, “the public will accept [Doc] as an idealistic figure—or will they find him funny.” And again Pal maintains, “We didn’t make it so,” while admitting that “some situations might provoke a laugh,” though “Not a bad laugh!”

Again we return to the question: “Do you think,” asks Harmon, “the public will accept [Doc] as an idealistic figure—or will they find him funny.” And again Pal maintains, “We didn’t make it so,” while admitting that “some situations might provoke a laugh,” though “Not a bad laugh!”

Harmon brings up Philip José Farmer who “wrote a book all about Doc Savage, and…another called Tarzan Alive in which he theorized that all the great heroes of the thirties knew each other, and were even related in a family manner.” He asks, “Do you see making a picture where Doc Savage might meet some other great hero of the thirties—the Spider or G-8, or—?” Pal instantly nixes the idea. “We have one hundred and eighty one Doc Savage novels. We aren’t desperate for stories. We will stick with Doc!”

In the end Harmon, hungry for Doc Savage crossovers, would just have to content himself with Giant-Size Spider-Man #3 (June 1975) and Marvel Two-In-One #21 (November 1976), team-ups which paired the Man of Bronze with Spider-Man and The Thing.

THE END OF THE BEGINNING

Professor Gilbert, Almighty Wielder of the Weird,

returns to look at the second issue

of Marvel's version of The Man of Bronze

on Sunday, March 22

And don't forget to tune in on

March 7th for Gilbert's dissection of

the penultimate issue of

Unknown Worlds of Science Fiction!

Get your Fill of Professor Gil!

Professor Gilbert, Almighty Wielder of the Weird,

returns to look at the second issue

of Marvel's version of The Man of Bronze

on Sunday, March 22

And don't forget to tune in on

March 7th for Gilbert's dissection of

the penultimate issue of

Unknown Worlds of Science Fiction!

Get your Fill of Professor Gil!

Actually, there IS a movie tie-in edition of "Man of Bronze" -- kind of. It basically looks like every other Bantam printing of the first novel, with the famous iconic Bama portrait on the front cover, but has Kastel's movie poster of Doc Ely on the BACK cover. IIRC there's a small blurb on the front calling it the "Special Movie Edition".

ReplyDeleteOtherwise, good re-cap of the first b/w Marvel mag, Prof!

--b.t.

Gil,

ReplyDeleteMore first rate pulse-pounding pulp pondering!